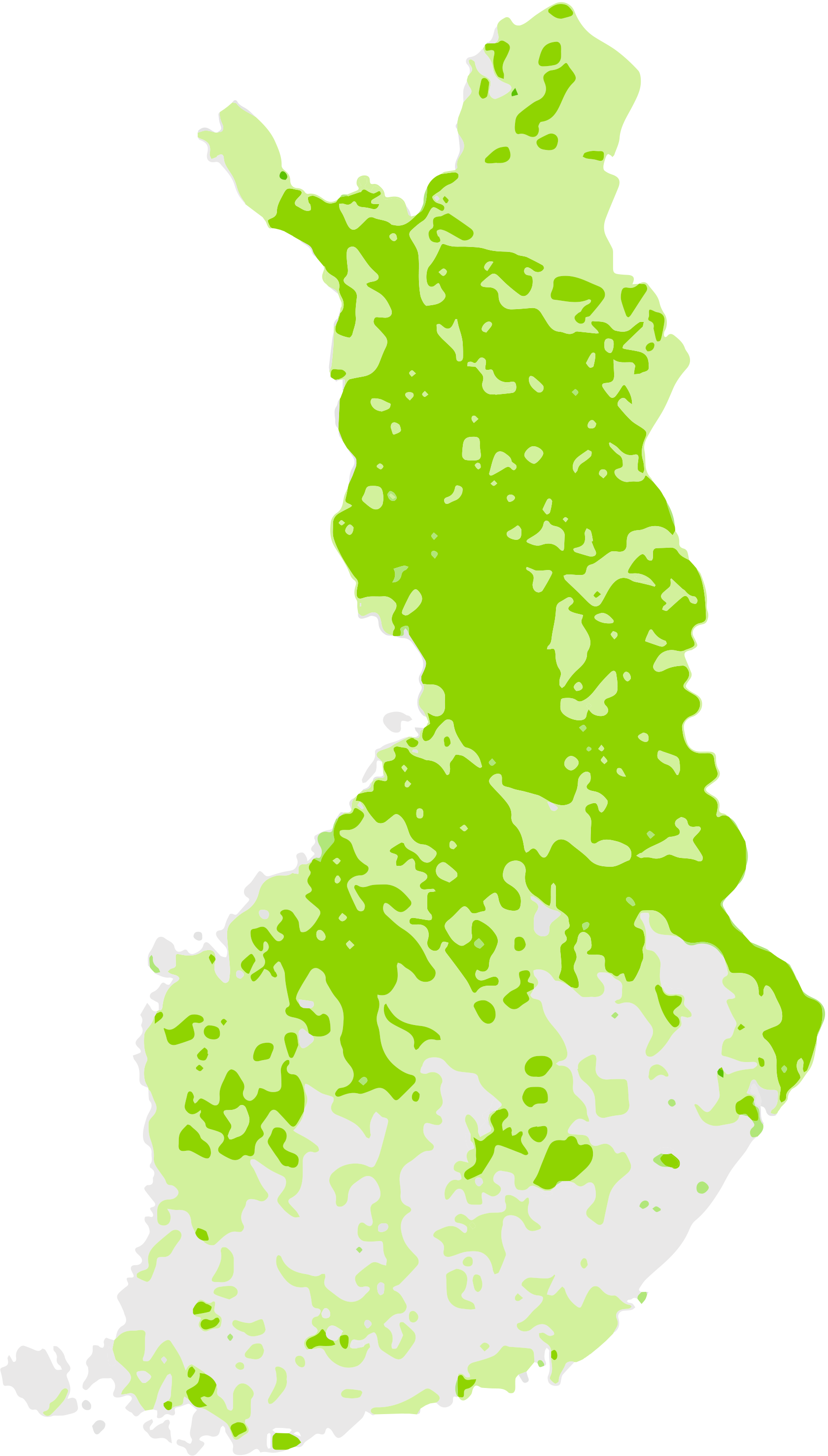

Peatlands cover over a quarter of Finland – a bigger share than in any other country. We are improving our methods for operating in peatlands and training our personnel and entrepreneurs in the new ways of working.

A quarter of Finnish forests grow on peatlands. About one fifth of the wood harvested annually in Finland comes from these peatland forests. The Natural Resources Institute Finland estimates that the annual felling possibilities from peatland forests are growing as the trees mature. These forests have a significant importance to their owners, but also for biodiversity, climate and our wood supply.

Peatlands are even more common in the region surrounding the planned bioproduct mill in Kemi than in Finland on average. The annual pulpwood consumption of the new Kemi bioproduct mill would be approximately 7.6 million cubic metres, and the region’s peatland forests are of economic importance both to our owner-members and for our wood supply.

Ditches were dug in over half of Finnish peatlands between the 1950s and 1980s. These ditches lower the water level, and this improves tree growth. These forests are maturing and reaching an age when their owners are set to benefit the most from them economically.

Peatland forests are carbon sinks

Peat is a plant-based, extremely slowly renewing organic material. Finnish peatlands are a huge carbon store, and forestry operations affect both this store and its carbon sink.

When dry peat decays, it causes carbon dioxide emissions, and decaying wet peat causes methane emissions. Both are greenhouse gases. Currently in Finland, trees growing on peatlands sequester more carbon than what is released from peat either naturally or due to forestry actions. Peatland forests are carbon sinks, as Finnish forests are as whole.

Peatland pose unique challenges

Due to the ditches, the growth of peatland forests has increased significantly, but it has also brought challenges, some of which we are just learning about due to new research.

Ditches are no longer dug in peatlands in their natural state, but the common practice is to maintain existing ditches.

Typically, peatland forests are less dense than forests growing on mineral soils, so the felling income per hectare is smaller; also, the quality of the wood is not as high.

When trees grow well, they themselves keep the water level stable. Problems occur during regeneration fellings: trees are removed, evaporation decreases and the water level rises. The common way to lower the water level again and to maintain tree growth has been to maintain the ditches. However, ditch maintenance typically causes leaks of nutrient and humus into the water.

Operating on wet peatlands is also more difficult and requires more planning, and is thus costlier than on mineral soils. Often, it requires a good winter and frozen ground. All this means that peatland forestry is less profitable than forestry on mineral soils.

Stable water level: crucial

Thanks to new research, we know that the crucial thing when operating on peatland forests is to try to maintain a stable water level at about 30–40 cm below the surface of the peatland. If we achieve this, we can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and maintain the good growth of the trees. Why?

Because when the water level is at 30–40 cm, the majority of a tree’s roots have access to oxygen, but the thick pad of peat below that level is safe from decaying. Also, no significant level of methane is emitted in these conditions.

So, to summarize, all we must do concurrently is to maintain a stable water level and thus avoid nutrient, greenhouse gas and humus emissions, in order to maintain good tree growth, profitable forestry for forest owners and wood procurement for our mills. This might sound like a tall order.

It is not easy, but it’s doable. We already have solutions in our hands, and we are developing new ones.